Text by Persis Bekkering

Opening: December 18, 2025 / 6PM – 9PM

Dec 19, 2025 – Jan 31, 2026

Martin Groch — They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry

The gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Slovak-born artist Martin Groch. Groch currently lives in Brussels and works as an artist, cartoonist, and graphic designer. The exhibition features new works on paper titled They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry.

As part of the exhibition, Clauda will host the launch of After Giotto, Everything Went to Shit, a new publication by Persis Bekkering and Martin Groch, to be published by Utopia Libri.

BIO:

Martin Groch (1990)

is an artist, illustrator and graphic designer currently based in Brussels. Throughout his diverse practices, he is interested in the narrative expression of images, desiring to find explosive visual forms on the edge of the readable. He prefers to situate himself in the tradition of drawing and cartooning, even where he uses paint and brush, and feels strongly drawn to the publication form and the reproduced image. He is the author of Sweathearts (Abyme 2024), a typeface and comic book, published by his dear friend, the late John Morgan.

Born in Košice (Slovakia), Groch has been professionally active as a graphic designer and artist at least since 2013. He first trained in graphic techniques and typography, at Umprum in Prague among other institutions, which he left precociously. From 2019 to 2020, he was a resident at the Jan van Eyck Post-Academy for Art, Design and Reflection in Maastricht. Among his frequent collaborators are Tim+Tim Studio, Jakub Samek, Robert Jansa, Peter Bosák, and Nana Esi (Atelier Brenda).

At the invitation of prof. Natasha M. Llorens (KKH Royal Institute of Art Stockholm) in 2020, he participated in a project titled Art-Rite, reinterpreting the iconic cheap art newspaper from 70s New York. At KKH, Groch was also invited to give workshops and lectures. He has since taught at the Royal Academy of Arts Antwerp, Ensad Nancy, and in the current season, at HfG Karlsruhe. Previous exhibitions of his work include the Jan van Eyck Academy Maastricht, PLATO Ostrava, the Salone del Mobile Milan.

Persis Bekkering (NL)

is a writer and critic, engaging with a wide spectrum of artistic disciplines. She is interested in forms of expression that account for the permanence of crisis in the contemporary world. She is the author of two novels in Dutch, A Hero’s Life (2018, shortlisted for the ANV Debut Prize) and Excess (2021, shortlisted for the BNG Bank Prize for Literature). Her novella Last Utopia is published in English translation by the Jan van Eyck Academy Maastricht. As a writer, performer, conversation partner and dramaturge, she collaborates with artists such as Martin Groch, Dora García and Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe. She also teaches creative writing at ArtEZ University of the Arts in Arnhem (NL).

.....

“Why are you drawing women so ugly?” my father asked me when I was a teenager. Around the same time, my mother remarked that drawing like this makes me one of those old men — she must have meant those sleazy, sad, or bankrupt ones from the generation of my father or older. Alcoholics, failed poets, bad fathers were around then as they are now. Both my parents must have been suspicious of what would become of me. I don't know what I answered them. I draw them like I find them most interesting.

I have been taught it is not good art to draw a black outline, to draw eyelashes, and that good artist should hold back when depicting that glitter in someone’s eyes. It was the late modernist tradition with an eastern Czechoslovak-Hungarian flavor I grew up with. That is inevitably a matter of the place and class one is born into; that was my first inheritance. And then I discovered comics. Suddenly I was invested in the opposite of the moderate, restricted modern style of painting (that style that which evidently was never meant to be restricted, but that's how it appeared to me, at that point in my life). I asked my father, who was a publisher at the time, if I could ever make money by applying ink on paper in order to create images, and he said – yes, sure.

Now I mostly use black brushstrokes. I draw make-up, jewelry, and hair, sometimes more visibly than any facial features, and my references are the kind of images meant to be read - cartoons, gothic paintings on wooden panels, or those characters in the mid-19th-century work of Wilhelm Busch, Max and Moritz. I love Krazy Kat, I like Yuichi Yokoyama and his “New Engineering,” where comics get as loud as they possibly can. I like American underground comics, I like those dancing, breathing, confused and overwhelmed characters which one might find in comics from Belgium, France, the States, Japan. There is something about that mechanical line.

I draw people as types or as specific people. I draw characters. Women, men, animals. Sometimes I doubt whether a typological depiction of figures is lazy — as I was being told —, but then again, typology is also a way of seeing, a way of catching something shared between people. Typology is not only repetition; it is also the place where the hand is balancing between something automatic and something inventive, between what is programmed and what aims to be free. Because otherwise — what is the alternative?

There is much debate about where to draw the line between drawing and painting, but I like to call what I do ‘drawing'. The history of drawing speaks to me the most. It is the closest I have come to writing. I'm always trying to hit that edge of readability. I often buy and consume a catalogue or a book accompanying a show, and that is what causes me the most joy. That is how I relate myself to so-called fine art. The format of a catalogue, a book with a reduced image quality, it tears off the aura of the work. The work of an artist is thrown into the mundane circulation of everyday life. Exciting. Reproduction flattens the work. Finally it becomes a picture plane I can orient myself in. I also feel drawn to the writing that comes with it – essays, interviews, captions. I tend to enjoy any art in that mixed form, sometimes more than the exhibition itself.

I am from a country where cartoon, as a practice, does not have its own name, and as a discipline no terms to work with. Cartooning is not reflected upon, exists just in fragments. One might aspire to be “karikaturista”, which means to do caricature, or to do “kreslený vtip”, which means to draw jokes. And who wants to be that? Yet there is something so captivating in how the pen in interaction with a sheet of paper is able to do anything within a very limited space, to depict scenes of any kind, to build mise-en-scènes. I’m sometimes telling myself this is the closest I can get to writing. To do cartoons is to count with the reader, to be read. I draw a head and it is a circle with eyes, that circle is a line and eyes are dots; I like to think “how is it possible we can read that abstract form?”

“One good reproduction is worth a thousand poor originals.” My works are rather small in format, and there is a reason for that. I want to have them scanned at the best possible quality I can achieve, in order to be able to put them to work, to make a reproduction. Standing side by side with the scanner has become something that takes up a significant part of my working time. If one looks at comics originals — American, French, Japanese, the older ones that belong to history — there is, for many, a charming mess created by functional marks: pure cyan pencil underneath the black drawing, marks left for printers and editors, notes on coloring or cropping the image. There is always the consideration of scale involved, of how much one can or should reduce a drawing to have the right impact within the chosen format. With reproduction one is losing something but there is a good and fair exchange: work that is reproduced is meant to be engaged with differently than the original; it is meant to be consumed with appetite, it is not precious. Reproduction, much like a book without a spine, has no authority.

When I made the works for “They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry,” I was not thinking about the possibility of an exhibition at all; I thought I would show them in a magazine or in some printed form or another. And so this work was always pleasurable to do, without pressure. I have an immense interest in the structural and emotional meaning of them. I happily accept it if they stay on the margin.

I have strange ambitions. I wish to be like Tove Jansson — a failed painter who was at her best making cartoons, illustrations and children’s books. I wish to have something of Carol Rama, who was fearless in drawing phalluses and unsettling women — things you don’t want to see but cannot look away from. It doesn’t feel comfortable, and it hits with the kind of impact I admire. And something of the Hernandez Brothers and their Love and Rockets series: where the characters – women – are as much typologies, shaped by a learned way of drawing, as they are alive. And body parts, in all kinds of forms, are everywhere — and they don’t mean “sex”, but even so. They’re juicy as hell. They might be angry. Not ugly at all.

Martin Groch, edited by Persis Bekkering

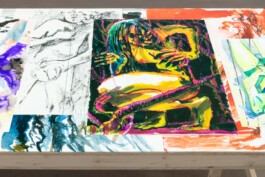

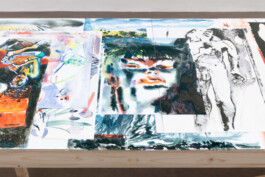

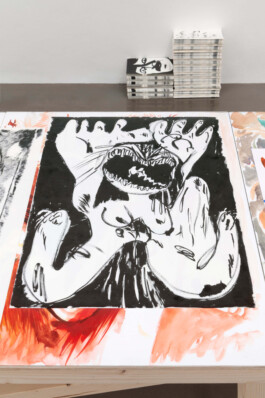

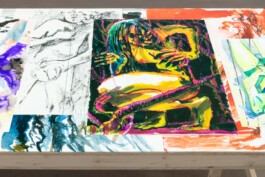

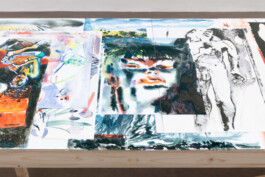

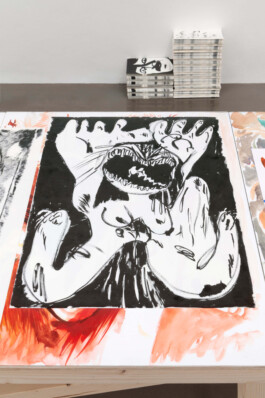

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Text by Persis Bekkering

Opening: December 18, 2025 / 6PM – 9PM

Dec 19, 2025 – Jan 31, 2026

Martin Groch — They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry

The gallery is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Slovak-born artist Martin Groch. Groch currently lives in Brussels and works as an artist, cartoonist, and graphic designer. The exhibition features new works on paper titled They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry.

As part of the exhibition, Clauda will host the launch of After Giotto, Everything Went to Shit, a new publication by Persis Bekkering and Martin Groch, to be published by Utopia Libri.

BIO:

Martin Groch (1990)

is an artist, illustrator and graphic designer currently based in Brussels. Throughout his diverse practices, he is interested in the narrative expression of images, desiring to find explosive visual forms on the edge of the readable. He prefers to situate himself in the tradition of drawing and cartooning, even where he uses paint and brush, and feels strongly drawn to the publication form and the reproduced image. He is the author of Sweathearts (Abyme 2024), a typeface and comic book, published by his dear friend, the late John Morgan.

Born in Košice (Slovakia), Groch has been professionally active as a graphic designer and artist at least since 2013. He first trained in graphic techniques and typography, at Umprum in Prague among other institutions, which he left precociously. From 2019 to 2020, he was a resident at the Jan van Eyck Post-Academy for Art, Design and Reflection in Maastricht. Among his frequent collaborators are Tim+Tim Studio, Jakub Samek, Robert Jansa, Peter Bosák, and Nana Esi (Atelier Brenda).

At the invitation of prof. Natasha M. Llorens (KKH Royal Institute of Art Stockholm) in 2020, he participated in a project titled Art-Rite, reinterpreting the iconic cheap art newspaper from 70s New York. At KKH, Groch was also invited to give workshops and lectures. He has since taught at the Royal Academy of Arts Antwerp, Ensad Nancy, and in the current season, at HfG Karlsruhe. Previous exhibitions of his work include the Jan van Eyck Academy Maastricht, PLATO Ostrava, the Salone del Mobile Milan.

Persis Bekkering (NL)

is a writer and critic, engaging with a wide spectrum of artistic disciplines. She is interested in forms of expression that account for the permanence of crisis in the contemporary world. She is the author of two novels in Dutch, A Hero’s Life (2018, shortlisted for the ANV Debut Prize) and Excess (2021, shortlisted for the BNG Bank Prize for Literature). Her novella Last Utopia is published in English translation by the Jan van Eyck Academy Maastricht. As a writer, performer, conversation partner and dramaturge, she collaborates with artists such as Martin Groch, Dora García and Benjamin Abel Meirhaeghe. She also teaches creative writing at ArtEZ University of the Arts in Arnhem (NL).

.....

“Why are you drawing women so ugly?” my father asked me when I was a teenager. Around the same time, my mother remarked that drawing like this makes me one of those old men — she must have meant those sleazy, sad, or bankrupt ones from the generation of my father or older. Alcoholics, failed poets, bad fathers were around then as they are now. Both my parents must have been suspicious of what would become of me. I don't know what I answered them. I draw them like I find them most interesting.

I have been taught it is not good art to draw a black outline, to draw eyelashes, and that good artist should hold back when depicting that glitter in someone’s eyes. It was the late modernist tradition with an eastern Czechoslovak-Hungarian flavor I grew up with. That is inevitably a matter of the place and class one is born into; that was my first inheritance. And then I discovered comics. Suddenly I was invested in the opposite of the moderate, restricted modern style of painting (that style that which evidently was never meant to be restricted, but that's how it appeared to me, at that point in my life). I asked my father, who was a publisher at the time, if I could ever make money by applying ink on paper in order to create images, and he said – yes, sure.

Now I mostly use black brushstrokes. I draw make-up, jewelry, and hair, sometimes more visibly than any facial features, and my references are the kind of images meant to be read - cartoons, gothic paintings on wooden panels, or those characters in the mid-19th-century work of Wilhelm Busch, Max and Moritz. I love Krazy Kat, I like Yuichi Yokoyama and his “New Engineering,” where comics get as loud as they possibly can. I like American underground comics, I like those dancing, breathing, confused and overwhelmed characters which one might find in comics from Belgium, France, the States, Japan. There is something about that mechanical line.

I draw people as types or as specific people. I draw characters. Women, men, animals. Sometimes I doubt whether a typological depiction of figures is lazy — as I was being told —, but then again, typology is also a way of seeing, a way of catching something shared between people. Typology is not only repetition; it is also the place where the hand is balancing between something automatic and something inventive, between what is programmed and what aims to be free. Because otherwise — what is the alternative?

There is much debate about where to draw the line between drawing and painting, but I like to call what I do ‘drawing'. The history of drawing speaks to me the most. It is the closest I have come to writing. I'm always trying to hit that edge of readability. I often buy and consume a catalogue or a book accompanying a show, and that is what causes me the most joy. That is how I relate myself to so-called fine art. The format of a catalogue, a book with a reduced image quality, it tears off the aura of the work. The work of an artist is thrown into the mundane circulation of everyday life. Exciting. Reproduction flattens the work. Finally it becomes a picture plane I can orient myself in. I also feel drawn to the writing that comes with it – essays, interviews, captions. I tend to enjoy any art in that mixed form, sometimes more than the exhibition itself.

I am from a country where cartoon, as a practice, does not have its own name, and as a discipline no terms to work with. Cartooning is not reflected upon, exists just in fragments. One might aspire to be “karikaturista”, which means to do caricature, or to do “kreslený vtip”, which means to draw jokes. And who wants to be that? Yet there is something so captivating in how the pen in interaction with a sheet of paper is able to do anything within a very limited space, to depict scenes of any kind, to build mise-en-scènes. I’m sometimes telling myself this is the closest I can get to writing. To do cartoons is to count with the reader, to be read. I draw a head and it is a circle with eyes, that circle is a line and eyes are dots; I like to think “how is it possible we can read that abstract form?”

“One good reproduction is worth a thousand poor originals.” My works are rather small in format, and there is a reason for that. I want to have them scanned at the best possible quality I can achieve, in order to be able to put them to work, to make a reproduction. Standing side by side with the scanner has become something that takes up a significant part of my working time. If one looks at comics originals — American, French, Japanese, the older ones that belong to history — there is, for many, a charming mess created by functional marks: pure cyan pencil underneath the black drawing, marks left for printers and editors, notes on coloring or cropping the image. There is always the consideration of scale involved, of how much one can or should reduce a drawing to have the right impact within the chosen format. With reproduction one is losing something but there is a good and fair exchange: work that is reproduced is meant to be engaged with differently than the original; it is meant to be consumed with appetite, it is not precious. Reproduction, much like a book without a spine, has no authority.

When I made the works for “They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry,” I was not thinking about the possibility of an exhibition at all; I thought I would show them in a magazine or in some printed form or another. And so this work was always pleasurable to do, without pressure. I have an immense interest in the structural and emotional meaning of them. I happily accept it if they stay on the margin.

I have strange ambitions. I wish to be like Tove Jansson — a failed painter who was at her best making cartoons, illustrations and children’s books. I wish to have something of Carol Rama, who was fearless in drawing phalluses and unsettling women — things you don’t want to see but cannot look away from. It doesn’t feel comfortable, and it hits with the kind of impact I admire. And something of the Hernandez Brothers and their Love and Rockets series: where the characters – women – are as much typologies, shaped by a learned way of drawing, as they are alive. And body parts, in all kinds of forms, are everywhere — and they don’t mean “sex”, but even so. They’re juicy as hell. They might be angry. Not ugly at all.

Martin Groch, edited by Persis Bekkering

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Martin Groch, They Are Ugly Because They Are Angry, photo Eva rybářová

Clauda

Wed – Thu 2p.m. – 7p.m.

Fri – Sat 2p.m. – 6p.m.

or by appointment

Veverkova 28,

Praha 7, 170 00

Czech Republic

We recommend parking at the Stromovka shopping center.

Antonín Jirát

+420 608 438 723

antonin@clauda.cz

Billing:

Clauda

Antonín Jirát,

Na Ovčinách 970/4,

Prague, 170 00

Czech Republic

IČO: 01168711

Clauda

Wed – Thu 2p.m. – 7p.m.

Fri – Sat 2p.m. – 6p.m.

or by appointment

Veverkova 28,

Praha 7, 170 00

Czech Republic

We recommend parking at the Stromovka shopping center.

Antonín Jirát

+420 608 438 723

antonin@clauda.cz

Billing:

Clauda

Antonín Jirát,

Na Ovčinách 970/4,

Prague, 170 00

Czech Republic

IČO: 01168711

Sign Up for Newsletter

Sign Up for Newsletter